All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

Commenting on Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s “Tabula Rasa,” a work for two violins, prepared piano and chamber orchestra Wolfgang Sandner says in the liner notes:

“What kind of music is this? Whoever wrote it must have left himself behind at one point to dig the piano notes out of the earth and gather the artificial harmonics of the violins from heaven. The tonality of this music has no mechanical purpose. It is there to transport us towards something that has never been heard before.” (Trans. from the German by Anne Cattaneo)

Write what you know? More pointed, write what you didn’t know until the moment something materialized, just out of reach, and you waited for it like a dream you could almost, but not quite, hold in your mind, and you wrote it, or something of it, or some barely ectoplasmic version of it.

The brilliant and prolific Dan Beachy-Quick catches hold of an essential something of this ephemeral moment in his new book from Milkweed: Wonderful Investigations, Essay, Meditations, Tales. “Wonder, to preserve itself, withdraws. It withdraws from the mind, from the willing mind, which would make of mystery a category.”

Dan describes some sort of hazy line, a faulty boundary—that marks the periphery: one side of the line is the daily world where we who have appetites must fill our mouths, we who have thoughts must fill our minds. The other side is within the world and beyond, where appetite isn’t to be sated, where desire is not to be fulfilled, and where thoughts refuse to lead to knowledge. And here I’m reminded of Odysseus in Hades, that liminal space between the living Odysseus and Odysseus not quite alive, and that equally liminal space that separates the shades of Hades from their own deaths. I’m thinking also of our own mortal dream states, that equally not-quite-here-not-quite-there compartment that we occupy when we write.

Beach-Quick continues, “I like the moment of failure that finds us on that line, abandoned of intent, caught in an experience of a different order, stalking the line between two different worlds and imperfectly taking part in both. Such a place risks blasphemy at the same time that it returns reverence to risk.” (p. xvi) And here I’m thinking how critical this notion of “blasphemy” is to the artistic process – by which I mean, that ambition itself must fail for something of value to be created.

HAMLET

Denmark’s a prison.

ROSENCRANTZ

Then is the world one.

HAMLET

A goodly one; in which there are many confines,

wards and dungeons, Denmark being one o’ the worst.

ROSENCRANTZ

We think not so, my lord.

HAMLET

Why, then, ’tis none to you; for there is nothing

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so: to me

it is a prison.

ROSENCRANTZ

Why then, your ambition makes it one; ’tis too

narrow for your mind.

HAMLET

O God, I could be bounded in a nut shell and count

myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I

have bad dreams.

GUILDENSTERN

Which dreams indeed are ambition, for the very

substance of the ambitious is merely the shadow of a dream.

HAMLET

A dream itself is but a shadow.

ROSENCRANTZ

Truly, and I hold ambition of so airy and light a

quality that it is but a shadow’s shadow.

Isn’t it just so on both counts? Count one: the creative act wants the taboo of border crossings: Think of Macbeth here, that a phantasmagorical realm of witches, nightmarish apparitions, cannibalism, and thickening light. Count two: we can’t (as I’ve just said) approach that border without sacrificing ambition. Think of Odysseus’s libations at The Grove of Persephone:

Or Thoreau, meditating through Concord:

For my part, I feel that with regard to Nature I live a sort of border life, on the confines of a world into which I make occasional and transitional and transient forays only, and my patriotism and allegiance to the State into whose territories I seem to retreat are those of a moss-trooper. Unto a life which I call natural I would gladly follow even a will-o’-the-wisp through bogs and sloughs unimaginable, but no moon nor fire-fly has shown me the causeway to it. Nature is a personality so vast and universal that we have never seen one of her features. (Henry David Thoreau, “Walking”)

(Photo courtesy of Wells Horton, http://wells-horton.smugmug.com/)

Seen differently, say you come to one of those road signs that reads “Self-Storage, 5 Miles.” It might as well be the Grove of Persephone you’re descending toward. You can stop at the Cumberland Farms and get all the ingredients you need to meet the denizens of the Other World. You’ll find them in the libations section. Carton of milk. Jar of honey. Box of wine.

Even so, for the poet as for Odysseus, the world keeps on ending. It’s the nightly apocalypse of the soul.

Thomas of Solano was the first Franciscan to compose a biography of St. Francis of Assisi, and it was also Thomas who rewrote the Church’s Prayer for the Dead into the classic Dies Irae, “Day of wrath, of doom impending/David’s word with Sybille’s blending/Heaven and earth in ashes ending.” One more instance of how, from William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book, from The Divine Comedy to Piers Ploughman and Chaucer, apocalyptic references and apocalyptic images rerun though the Middle Ages, which isn’t surprising since so much of these times felt like that last time. Not least the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which were clearly cut out for the four deadly Horsemen – war, famine, plague, and death – and hell on earth and their retinue of visionaries and scourging flagellants, massacres, flaming pyres, mass burnings of beggars and vagabonds and witches like Joan of Arc and especially of Jews, who (as ever) obstinately refused to see the light. “What people said,” noted a Norman priest, “was that the world was ending.”

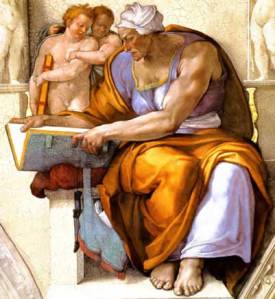

And people were right, of course. The world kept right on ending. Even the Renaissance bulged with reminders and predictions of apocalyptic prophecy. Even in the Sistine Chapel, pagan prophetesses rubbed elbows with their male Old Testament counterparts. In the Borgia apartments that Pinturicchio decorated, the mysteries of Osiris prefaced the mysteries of Christ.

And people were right, of course. The world kept right on ending. Even the Renaissance bulged with reminders and predictions of apocalyptic prophecy. Even in the Sistine Chapel, pagan prophetesses rubbed elbows with their male Old Testament counterparts. In the Borgia apartments that Pinturicchio decorated, the mysteries of Osiris prefaced the mysteries of Christ.

So, back to our writing room, our watchtower, where we learn to let the poem keep its vigil for us, where like intimations of the Apocalypse we are flexible; we’re both pessimistic and annihilating (we denounce the suspect prophets who peddle alleged absolutes – read here, our ambition for the narrative – and when I say narrative, I mean of course, the lyric), but at the same time, we’re optimistic and promissory, awaiting the prophet or the witness with her monolithic, all-resolving message.

Self-centered, self-fascinated, we (all of us) are loath to concede that we (each of us) is not central to the cosmic scheme of things, and in this view apocalypse, however tragic, reassures. Time and space, it says, are about our relation with something transient as it is transcendent. Call it art. Call it “the nothing we know too well.”

Remember how promising Genesis was: “And all the earth was one language, one set of words.” (Genesis 11:1) Turns out “It is only insomnia” we get, with its muddle of languages, double helixes of words – and with a sudden and quiet click the camera has changed its focus.

“Many must have it.” We need the public and routine world so that we may shore ourselves up from that other vision. But for the poet, insomnia is perhaps a more privileged philosophical state than we (or the old waiter) thought. Each night, in those moments before we go off to sleep (or offer libations to the unconscious, to bring the poem in, to keep the poem away) we are alone. Sundered from others and their world, passing into the shadow that is the simulacrum of you-know-what. Now I lay me down to sleep is the record of the anxiety this moment begets. I pray the Lord my soul to take. But first, please, one good poem. Well, any kind of faith is somehow more convincing when it permits itself a sense of humor. (That blasphemous prayer in “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” gathers more meaning precisely because it comes from a man who didn’t take blasphemy lightly.)

“Many must have it.” We need the public and routine world so that we may shore ourselves up from that other vision. But for the poet, insomnia is perhaps a more privileged philosophical state than we (or the old waiter) thought. Each night, in those moments before we go off to sleep (or offer libations to the unconscious, to bring the poem in, to keep the poem away) we are alone. Sundered from others and their world, passing into the shadow that is the simulacrum of you-know-what. Now I lay me down to sleep is the record of the anxiety this moment begets. I pray the Lord my soul to take. But first, please, one good poem. Well, any kind of faith is somehow more convincing when it permits itself a sense of humor. (That blasphemous prayer in “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” gathers more meaning precisely because it comes from a man who didn’t take blasphemy lightly.)

Your next door neighbor, that woman of action who is right now in the middle of the night washing out the drain spouts with the garden hose, can give herself to the ritual that is absorbing enough to make one forget the Void. But you, poet, in your watchtower with your door closed, bringing the obscure future into focus with the yet undiscovered narrative, your night vision, you are in another boat. You’re an observer, a sentry, whose job (alas, not so very well compensated) is to keep a wakeful eye on the uncanny presences behind all human action, and even now and then to take the enormous risk of venturing out into the world in all its gloaming, that world where, as Auden puts it in “As I Walked Out One Evening”:

The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed . . .

And so you earn your insomnia.

It’s a lonely vigil, but you knew that. It’s a solicitous solitude, in which all beings recede to a distance. Lucky you have that radio. You can tune in on Minneapolis and Seattle and San Luis Obispo and hear distant voices speaking to you through the night. And also, you have imagination, and you can see people getting up in Minneapolis and grinding coffee or riding in the white taxicabs of Seattle or that youngish man slumping down at the bar of a tequileria-by-the-sea under the dancing TV phosphors, a late game he’s got money on, an advertisement for insomnia.

In our newer version of the world, the one that lapped Genesis five hundred years ago, people are at once very far off and painfully close. You don’t have the faith of the nun, and the code of the gambler is available to you only intermittently in your pursuit of that narrative that comes only by letting go of it, giving it more line.

Waiting.

You hover between those worlds in the lucid wakefulness that makes peace with You-Know-What. It may not seem much perhaps, but it’s something, and if the poem announces itself, it’s more than something. Besides, there’s always the possibility of sleep before dawn.

There’s the guy with the eye patch. Even he gets it. So I tell him about the road sign, and he gets that, too. The charcoal leaking onto everything. Sheets. That paper thing that shows off your sorry charcoal-covered ass, and he asks about the folks, whether they know, and you show him how raw your fists are from beating on the winter coats.

We enter a place, we say, “Now here’s an experience I want to write about, here’s a narrative that needs telling.” But to get there, as I say, we enter a place, you know that place, how it feels. It’s a grove, defined by certain and uncertain depths (knowable, unfathomable), and to enter there we find that experience (narrative) wants to fend off all language.

Language, of course, is a piss poor substitute for the subtleties we communicate so easily with our faces, with our bodies, with our hands, with our songs, and even so, with our paintbrushes and chisels and keyboards. The language that we hear is the language of dream that we don’t so much access as withdraw into: say, the dream of watching the dawn break crooked over the sea. To this zone belongs the marvelous chiaroscuro reveries of landscape, dawn, and twilight.

Here’s how Beckett finds that terrain in The Unnamable: “Thus as his body set him free more and more in his mind, he took to spending less and less time in the light, spitting at the breakers of the world; and less in the half light, where the choice of bliss introduced an element of effort; and more and more and more in the dark, in the will-lessness, a mote in its absolute freedom.”

Or as Ben Lerner writes, almost as a koan, in his “Mean Free Path” (Copper Canyon, 2010)

What if I made you hear this as music

But not how you mean that.

It turns out that we, each of us, constitute the so-called living proof that life is a wick, joy a filament. For example there was the time I thought I was dying (in that more immediate sense) and spent three days stretched prone on the river rocks, fingering the rills and vales of what I thought was left of my brain. The doctor described stem, obdula, hatch, and vault. He said, “There seems to be signs of trouble in the lobe that stores words like chiffarobe, mewl and mauve, hemstitch and metastasize.” Some mid-dim cortex he probed for signs of life with swivels, switches, dials, and knobs didn’t make the music he (we) needed to hear. Electrodes cabled me to boxes that issued clicks like crickets, only slower, more calculated. The tech-man let me listen and I picked out a certain pulse, like the clockwork of an erratic toy. But the doctor planted his hand on my shoulder, swallowed his words.

You know the famous actor, might have been Olivier, who once during a performance lost his way in Hamlet and for minutes went on in with some brilliant and seamless patter, an aural helix of nonsense syllable until somehow the lines reconnected from the void. Like that.

Special note: it turned out that my problem, that time anyway, was a degenerative condition of the inner ear called Meniere’s disease — a condition for which, if you’re lucky, every test result reads “essentially normal” — and you are, but for the persistence of vertigo. And everything was more-or-less normal. That the vertiginous experience is utterly predictable in its lack of predictability makes the condition a symptom of, well, being human.

When my son was little and we took long drives in the car with symphonies blaring — he liked taking long drives in the car (back roads only, please) — he said once that he liked the Schumann piano concerto best because it was the loudest of all. He hadn’t yet discovered Pink Floyd. He would. Play it loud. You can, too.

The more willing we become to let go of the melodies we know, fellow moss-troopers, the louder grow the melodies we do not.

P.S. Please keep in mind manuscript reviews and mentoring.

JL

Helen Marie Casey

March 19, 2012

Thanks so much, Jeffrey. A quite lovely addition to my day! Blessings.

Helen Marie Casey

carlen1717

March 19, 2012

“Wonder, to preserve itself, withdraws. It withdraws from the mind, from the willing mind, which would make of mystery a category.” — So, so, so much here, Jeffrey. I haven’t known Dan Beachy-Quick’s work well enough at all, so I’m glad for this quite remarkable introduction. Couldn’t make the gong work (if you meant it as a link), but everything else came through, and didn’t. Loud and clear (by which well, you already know what I mean).

Thank you.

Carlen

Susan Elbe

March 19, 2012

Thank you for this, Jeffrey. I’ve been in love with the unsayable my whole life, and “beating on the winter coats.” Yes.

Nancy Mitchell

March 19, 2012

Dot to dot, again you make the graceful leaps to connect these continents of thought. I wonder, be ye a friend of Bachelard?

Nancy Mitchell

Jeffrey Levine

March 20, 2012

A fan, certainly.

HeidiMarie Densmore

March 19, 2012

Jeffery, You prose begs for a new name. A symphony of thought.

Ellen Doré Watson

March 20, 2012

All what they said. I don’t read blogs. But for yours.

Jeffrey Levine

March 21, 2012

Thanks Ellen. I’ll try to earn it.

Kathleen McCoy

March 28, 2012

Thank you. I’m trying daily to “let go of the melodies [I] know . . .” to trust a newer music.

Linda Stryker

November 12, 2012

Hi Jeffrey,

You won’t see this because it is connected with the March offerings of your fans. But I cannot imagine what your mind is like to spring forth these sapphires of joy and beauty into the world. “. . . as music / But not how you mean that.” Your blogs are SO much nourishment for the soul, that I learn how much deeper I must dig into the soil of the spirit, of the human, to find the gold underneath the tinfoil and plastic. Thank you, thank you. I am blessed.

Jeffrey Levine

November 12, 2012

So astonishingly sweet, Linda. I am blessed to know you.